Sunday, 30 March

|

| We're all somebody's meal one day |

Good Morning

Jack…

I was caught

in the rain yesterday while on a long walk.

My clothes were drenched but it didn’t matter. It’s spring and the rain wasn’t cold. No more freezing nights. Soon we will switch from heater to air

conditioner here in North Carolina. But

for a short period there won’t be need for either. Today is right for opening windows and

letting the breeze sweep all the winter’s cabin fever from the house.

Friday a

woodpecker came knocking. He was right

above the window to my room. They really

are quite loud. You’d think they were

driving nails with their bill. How does

their brain take all that pounding? Terns

that spend their life diving into water after fish have a similar problem. Several times each day they collapse their

wings and make a high dive attack at their intended meal. I’m told smacking your head repeatedly does

take its toll and they aren’t likely to live more than three years. What do you think happens? Do they slowly knock themselves senseless to

the point of senility? Maybe their vision

becomes blurred or they start seeing double.

It’s not like they can go to an optometrist and get fitted for

corrective lenses. Every head throbbing

dive becomes a lucky miss for the fish. Eventually

it gets to be too much. How does a bird

process the headaches and all this frustration?

Don’t forget their nagging hunger pangs.

Then there are the youngsters. You’re

no longer part of a team providing food for a hungry nest. Your spouse is left with all the work. It just won’t do. Wanted:

healthy tern to replace the worn out one seen sitting lethargic by the

water’s edge. Life is for the

young. Animals in nature don’t enjoy

their golden years. There aren’t any to

enjoy. Your sorry carcass simply becomes

someone else’s nutritious meal. It’s

probably not long in coming, either.

Most every

warm-blooded animal gets hungry on a daily basis – birds especially. They have to fly to stay alive and they don’t

have the luxury of carrying around any body fat of consequence. You ever see a robin with love handles? If a bird on a limb looks plump you can be

guaranteed it is only because they’ve fluffed up their down for warmth.

So, yes, in

the dog-eat-dog world of Mother Nature there is no need for hiring a janitorial

service. If you’re that worn out tern

resting at the water’s edge and you hear “Clean up on Aisle 7” – you can rest

assured they are talking about you. The best

you can hope for is a humane death of having some ravished predator first bite

into the back of your neck. Lights out.

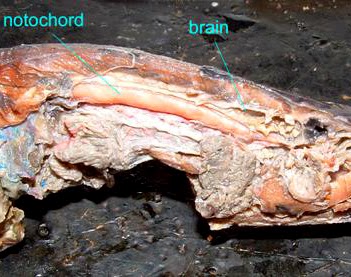

If we’re

open-minded about the matter we should probably feel gratified that our spent

selves provide a meal for more than one worthy individual. Usually there’s a vertebrate to provide the ceremonial

coup de grace. But they rarely pick your

bones clean. There’s too little left to

make it worth the effort of an animal carrying around a large stomach. Now it’s a race among the insects. Flies are quick to sense the aroma of your

decay and gladly lay their young amidst your tissue. Of course, you can never count out the

energetic search of the enterprising ants.

Now they truly will pick your bones clean. How many times have you witnessed a parade of

these busy-bodies streaming into the eye socket of some dearly departed

animal? By the end of the day, two at

the most, every sinus and cranial cavity becomes remarkably spic and span.

I suppose I’m

still a bit touchy about being eaten. I

can’t grasp the aesthetic beauty of being systematically torn limb from limb

and devoured. If that isn’t bad enough

then I have to further endure the humiliation of being defecated. Now doesn’t that make for a classic before

and after picture comparison? No, I much

prefer being consumed by flame. You can

scatter my ashes about the base of a desert mesquite bush. It’s so much more discrete. They have such fastidious manners when it

comes to feeding.

Love,

Dad