Mortality on a Global Scale

29 August 1949

The Russians detonate their first atomic bomb at Semipalatinsk, Kazakh SSR and become the second nuclear power. The United States was startled at having lost their nuclear monopoly so soon. Julius and Ethel Rosenberg became the first American civilians executed for espionage after having been convicted of passing nuclear weapons secrets to the Soviet Union.

RDS-1

The Soviet Union's first atomic bomb was comparable to America's Gadget and Fat Man with an explosive force of 22 kilotons of TNT. It was an implosion type weapon with a solid plutonium core. The United States gave it the code name of Joe 1, after Joseph Stalin.

Joseph Stalin

The alliance between the Western democracies and the Soviet Union during the war with Germany was always a matter of necessity, the marriage of convenience. The leaders of East and West shared few convictions and regarded each other with suspicion. Development of the atomic bomb was not a matter to be trusted with Stalin's Russia although the Soviet leader had his own sources within the Manhattan Project and displayed little emotion when America's President Truman spoke of a miraculous new weapon during their meeting in Potsdam. The lessons learned from the Great Patriotic War meant Russia was safe being second to no one and no Soviet leader, especially Stalin, would tolerate a world of American nuclear hegemony.

Harry Truman

Fear of Nazi Germany led to the development of the atomic bomb but with Berlin's surrender and bitter conflict continuing in the Pacific it seemed only natural to President Truman for him to order the use of this weapon in hopes of bringing the war with Japan to an end. Japan's unconditional surrender following the destruction of Hiroshima and a second atomic attack on Nagasaki brought a rapid demobilization of American military forces. Yet events quickly demonstrated that the perceived interests of the United States and those of the Soviet Union were in direct conflict.

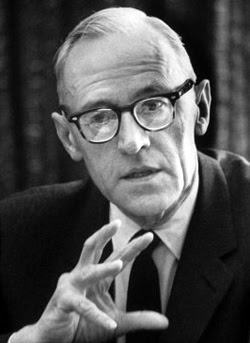

Dean Acheson

Secretary of State Dean Acheson had not anticipated military action by Communist forces in North Korea when he placed South Korea outside America's vital interests. Stalin, in turn, was surprised by the determined military response of the United States to developments on the Korean peninsula. Both countries quickly learned it was dangerous to miscalculate the other. The Korean War more than any other single event made clear a Cold War did exist between the globe's two emergent super powers.

Dwight Eisenhower

President Dwight Eisenhower, famed for overseeing the successful amphibious assault at Normandy in 1944, was determined to keep military costs to a minimum by relying on the threatened use of nuclear weapons in response to any military move on Western Europe by the Soviet Union's still large conventional army. Nuclear bombs and the means of delivering them was vastly cheaper than maintaining armed divisions.

John Foster Dulles

The ardent anti-Communist John Foster Dulles, Secretary of State under Dwight Eisenhower, was a strenuous proponent of massive retaliation, believing that releasing unrestrained force was the best deterrence to aggression. During the course of the 1950s Russia's own massive retaliatory power grew placing increased dependence on the credibility of America's nuclear threat. Citizens of Berlin, for instance, could only wonder whether the United States government was willing to risk destruction of its own cities in defense of this German city isolated deep within the Communist block.

Maxwell Taylor

General Maxwell Taylor, Army Chief of Staff under Eisenhower, called for a Strategy of Flexible Response. His argument for an American military capable of handling threats with conventional weapons would require enormous increases in defense spending and his belief in funding the means to fight limited wars found a receptive ear only when John Kennedy entered the White House. Within a couple of years President Kennedy introduced American troops into Southeast Asia and Maxwell Taylor would serve briefly as Ambassador to South Vietnam.

Herman Kahn

Herman Kahn made his reputation for speaking the unthinkable while employed at the RAND Corporation whose mission it was to freely explore the range of options available in thermonuclear war. His detached approach to gaming the catastrophic made him the basis for the bizarre, mad character that was the centerpiece of the motion picture Dr. Strangelove.

John von Neumann

Oskar Morgenstern

Two less flamboyant colleagues of Herman Kahn at the RAND Corporation were the celebrated mathematicians John von Neumann and Oskar Morgenstern. Their work in game theory led them to believe in the ultimate interdependence of the United States and the Soviet Union. The two nation's fates were linked and the decision making of each would ultimately require keeping the interests of their potential enemy always in mind in order to prevent antagonisms from getting out of hand. A practical application of this mindset occurred in the peaceful remedy to the Cuban Missile Crisis where each side avoided backing the other into a corner.

Henry Kissinger

This obscure Harvard professor gained national attention with the publication of his book, Nuclear Weapons and Foreign Policy, in which he argued that military means and diplomatic approaches are not separate ventures but interrelated when arbitrating differences between confrontational nations. Kissinger would become a seminal adviser to Richard Nixon during a period of relative rapprochement between America and her Cold War adversaries China and the Soviet Union.

Related Topics:

OVER EASY

No comments:

Post a Comment